It’s not unusual for Kimberly Mullen to get kicked, scratched, pushed or threatened during one of her shifts as a registered nurse in the telemetry unit at Kaiser Permanente’s South Bay Medical Center in Los Angeles.

It’s considered part of the job when dealing with patients who are sometimes confused, frustrated and feeling a loss of control in an unfamiliar hospital setting, she says. Still, she’s thankful she hasn’t fared worse, like one of her coworkers who was attacked by a patient’s family member.

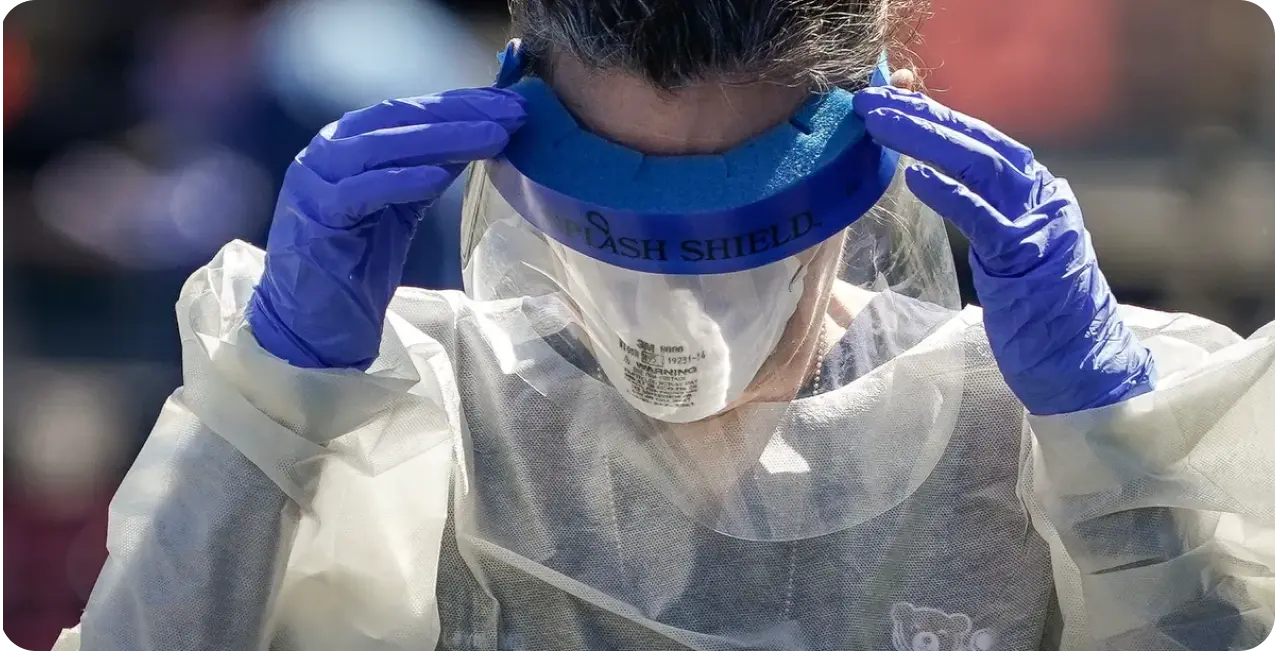

Mullen and millions of other healthcare workers nationwide are becoming accustomed to workplace violence, which can range from verbal abuse and threats to physical violence and even homicide.

The degree to which the pandemic has exacerbated the problem still isn’t entirely clear, though a number of attacks already have occurred this year.

Yelling, name-calling and shouting obscenities are now daily occurrences, and “that did not use to be the case,” said Hannah Drummond, an RN at HCA’s Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina.

Workers in the healthcare and social service industries experience the highest rates of injuries caused by workplace violence and are five times as likely to get injured at work than workers overall, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Those incidents have risen nearly every year for healthcare workers since the BLS began tracking them in 2011.

Sometimes they turn fatal. On average, 44 workplace homicides to private healthcare workers occurred each year from 2016 through 2020, according to the BLS.

Currently, there are no federal requirements healthcare employers must follow to protect employees from workplace violence, though the Occupational Safety and Health Administration offers voluntary guidance. A handful of states have rules for employers or laws penalizing offenders, putting much of the responsibility on individual hospitals.

Some nurses say the hospitals where they work have protected them effectively during the pandemic, citing measures like ongoing visitor restrictions and workplace violence prevention programs often spearheaded by labor unions or mandated by state law.

Others disagree, and say a lack of security, training and staffing challenges worsened by the pandemic are hindering their ability to provide timely, adequate care to every patient, resulting in patient and family frustrations that sometimes turn violent.

‘Less and less resources to care for patients’

This comes as hospitals deal with unprecedented staffing shortages. They are unlikely to abate anytime soon as widespread stress and burnout spurs healthcare workers — especially nurses — to consider leaving their roles.

A quarter of U.S. hospitals reporting their data to the HHS said they faced critical staffing shortages in early January, according to the agency.

Drummond at HCA’s Mission Hospital said a patient recently ended up striking one of her coworkers when staff couldn’t get into the room with pain medication quickly enough.

“So much of the frustration that’s taken out on nurses is justified, because each passing year we’re getting less and less resources to care for patients,” Drummond said.

So far this year, a number of attacks on healthcare workers already have occurred.